In late September, with my friend Beedle (of Fat of the Land fame) at the wheel, I rode shotgun on a long drive up to northwest British Columbia to go steelheading (more on that in a future post). We camped on the banks of the Kispiox, tributary to the Skeena, and sure enough the first big rainstorm of the season blew out the entire system just a few days after our arrival. So much for fishing.

Instead we took advantage of river out and explored the enormous country that is backwoods B.C., with an eye out for the mushroom trade that is such an integral part of this region.

In the hamlet of Kitwanga, just off highway 37 (only 700 miles to Alaska!), we found a buyer named Ave. He had his buy station—a simple wall tent with a wood stove—set up on a friend’s gravel lot just outside of town. As we pulled in Ave was in the middle of telling two First Nations men how they might go about finding mushrooms to sell. Otherwise the place looked deserted. It’s been a poor year for the matsutake harvest in B.C., with a record drought for most of the summer and early fall. We were told the Kispiox was as as low as it had been since river levels were first recorded, 70 years ago.

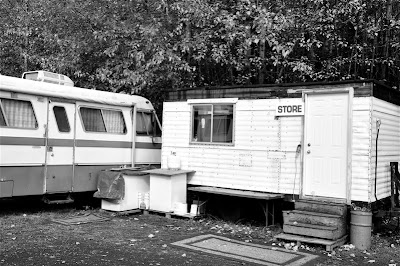

Known affectionately (or frighteningly, depending on your disposition) as “The Zoo,” this place has hosted as many as 1,500 mushroom pickers during the go-go years when matsutake fetched exorbitant prices on the Japanese market and pickers stuffed their pockets with cash for mushrooms. Now, after several so-so harvests and prices in the tank, it was nearly a ghost town. We saw only a handful of campers who had erected various forms of habitation, from simple tarp-and-stringer tents to more elaborate school-bus shacks.

The only one around was Grace, who has run the mobile general store here for the last decade. Grace had never seen the camp so desolate and she didn’t expect it to get any better with the recent rain. At $3 per pound, there’s little incentive—even poverty, it would seem—for a picker to hump mushrooms out of the bush all day. Grace explained that expenses (e.g., gas, food, auto repairs) can be as much as $100 a day, meaning 50 pounds of matsutake hardly covers your overhead. And on a year like this, picking 100 pounds a day is only feasible for the most knowledgeable of pickers.

Grace’s two football-sized dogs yapped away and she finally had to go back inside her trailer to nurse an illness. We were left alone in a nearly empty camp with a few indelible images: an outhouse in splinters on the ground, as if overrun by grizzlies; a burned out car that might have once been used as shelter more than transportation; a rusted and bullet-riddled trash-can spilling its refuse; a ruined tent slumping in the wind.

Images such as these might make you think about your next purchase of wild mushrooms at the local grocery store or farmers market. And by think I don’t mean to suggest you not buy them, only that you consider the supply chain that brings us these wild delicacies. The other day I saw porcini advertised for $40/lb and chanterelles at $15/lb. Even birch boletes, not nearly as choice as king boletes, were commanding a hefty $30/lb price-tag.

I’m not sure what the answer is. An astute commenter on one of my earlier posts noted that the inequities in the wild mushroom business are no different than in any other industry in America; wherever you look, those on the lower rungs are compensated proportionately less than those on top, yet without those people there is no top. As a recreational hunter, I can tell you that the knowledge, physical ability, and sheer cojones required to harvest large quantities of wild mushrooms in the wilderness are substantial. As a consumer and restaurant patron, I can tell you that the costs of eating these delicacies are dear. And as a member of the human race, I can tell you there are other hidden societal costs of not valuing the skills that put these foods on our plates. What are those costs worth?

Great post – I live near Nakusp BC, will you be coming home this way? Do you want to stop by and pick mushrooms here?

I appreciate the honesty of your reports. Buying direct from the pickers helps both the pickers and ourselves but we have to be willing to pay a price that compensates the pickers for the picking and the selling time and the overhead. This makes wild mushrooms more expensive than the cultivated ones but provides a wonderful eating experience. We can’t afford to dine out at the restaurants that serve wild mushrooms so we are grateful to the pickers that sell to us direct. We look forward to your next post and thanks for this blog.

I think you might be over-hyping this pickers to buyers hierarchy. I know two mushroom buyer/sellers who by no means are making all that much money. A modest income, yes, but not with huge overhead (in particular driving from BC to Idaho to California and back again) to buy from various pickers, and if it were broken into an actual hourly wage, it might be as low as the pickers receive in some instances. And the restaurant business is hardly known for the business to get rich in. Most restaurants (especially the ones selling foraged mushrooms) fail or are barely hanging on. I think it is actually an uneducated consumer who doesn’t know the difference between a good mushroom and a bad one, a good price and an inflated one who is to blame in these inequalities. And for that I applaud your blog in educating more of us about foraged foods.

Ruralrose – I hear that’s one of the more productive areas this year. Unfortunately I won’t be coming through. Next year!

Mike – It’s like buying salmon off the docks. There are many ways to skin a cat on this one, and pickers will no doubt find new avenues for their goods.

Rumblestrip – I don’t mean to over-hype anything. You’re right that the field buyers aren’t getting rich either, and I didn’t mean to suggest that they were. But like any other goods, there’s a fairly significant jump by the time the wild mushrooms reach the consumer and it’s unlikely in most cases the pickers benefit from the high price of what they pick.

Rumblestrip – Great points about the restaurant industry and their thin margins–and restaurant patrons. We all need to be more educated.

Great post,

It turns out ‘Matsutake’ and other similar Tricholomas are not as rare as once thought. New sources in China, Korea and even Finland have brought the price down considerably.

For example one can buy (localish) #1 Matsutake at most asian grocery stores for about 7 dollars a pound (around the Olympia area which is not known for its Matsi abundance).

This article reflects what I experienced in Crescent OR this fall. I went down there to gather interesting stories from mushroom hunters and found a ghost town. Perhaps that is the story…?

Check out these short Matsutake interviews on vimeo

-this one is with Kouy Loch of 2007 New Yorker Mag fame

LC will you or other FOTL readers be at the UW PSMC show? I will!

MPB – I’ll be at the show on Sat. You’re right about the supply/demand issues surrounding matsi–check out this post of mine from two years ago: http://fat-of-the-land.blogspot.com/2008/10/pining-for-pines.html Send me an email if you want to talk about your project. Cheers.

LC

Thanks for the response! I don’t have your email address but will keep an eye out for you at the PSMC exhibit.

MPB

bromax30@evergreen.edu